Remembering Jimmy Reid and his legacy

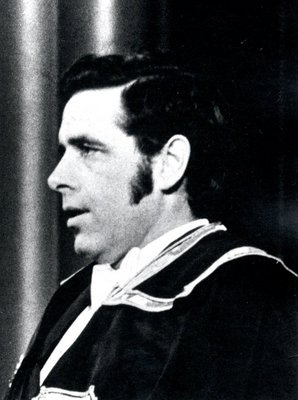

Jimmy Reid (born 9 July 1932) was a one of the towering figures of society and politics in post-war Scotland. He was variously a union activist, orator, politician, and journalist. Born in Govan in Glasgow, he first came to public prominence due to his role as spokesperson and one of the leaders in the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Work-in between June 1971 and October 1972. He later served as Rector of the University of Glasgow, making his famous declaration in his rectorial address that ‘A rat race is for rats. We’re not rats. We’re human beings’ and subsequently became a journalist and broadcaster. The address was reprinted in full in the New York Times.

Jimmy Reid (born 9 July 1932) was a one of the towering figures of society and politics in post-war Scotland. He was variously a union activist, orator, politician, and journalist. Born in Govan in Glasgow, he first came to public prominence due to his role as spokesperson and one of the leaders in the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Work-in between June 1971 and October 1972. He later served as Rector of the University of Glasgow, making his famous declaration in his rectorial address that ‘A rat race is for rats. We’re not rats. We’re human beings’ and subsequently became a journalist and broadcaster. The address was reprinted in full in the New York Times.

Formerly a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain and councillor for Clydebank, he was later a Labour Party member. He joined the Scottish National Party in 2005 and fully supported Scottish independence but died on 10 August 2010 after a long illness. His last major political project was to establish with Bob Thomson and others the Scottish Left Review magazine.

A year to the day of Jimmy’s death in 2011, the Scottish Left Review established the Jimmy Reid Foundation:

The Jimmy Reid Foundation has been established in memory of Jimmy Reid and to continue the legacy of radical political thinking his life represented. The Foundation is an independent ‘think tank’ and advocacy group focussed on practical, policy proposals for transforming Scotland which are based on analysis and investigation of the current Scottish and global political, cultural and social situation. The Jimmy Reid Foundation was set up to include the full range of progressive politics in Scotland. All the work of The Reid Foundation is based on a series of underpinning principles drawn from Jimmy’s own thinking:

• That society should be based on equality and social justice

• That people should have the democratic power to influence their workplace and social institutions

• That quality of life should be at the forefront of political debate and not an afterthought

• That justice can only come from peace and support for human rights

• That ideas, learning, arts and culture have the power to transform society and individuals

• That all these principles are underpinned by the importance of national identity and a vision for Scotland

In article for the Guardian’s Comment is Free at the time of his death (11 August 2010), I wrote:

The death of veteran trade unionist and socialist Jimmy Reid, just short of the 40th anniversary of the Upper Clyde shipbuilders work-in which he led, robs the radical left of a once-towering figure. Reid has been labelled ‘the best MP Scotland never had’. The only figure who has rivalled Reid’s significance has been Tommy Sheridan, as a result of the anti-poll tax campaign he led.

Reid had the kind of political imagination, flair and charisma which is sorely needed today as the now shrunken left faces up to the task of whether it can create an effective ‘coalition of resistance’ against the coalition government’s cuts and privatisation programme. Reid secured his place in the pantheon of popular revolts because, along with fellow Communist party members and fellow travellers such as Jimmy Airlie and Sammy Barr, he led not only one of the most important post-war struggles but one which did not end in glorious defeat.

Instead, the revolt ended after 18 months of hard struggle in a stunning victory with the nationalisation of the yards. This was one of the first nails in Edward Heath’s political coffin, as he became a lame duck prime minister who was forced to make umpteen U-turns.

The success and significance of the Upper Clyde shipbuilders’ struggle was threefold. First, faced with redundancy and closure, there was an innovation in tactics. The action was not a strike that put the workers outside the gates. Instead, the work-in maintained control of the yards, the half-built ships and equipment by occupying them. The work-in was also a challenge to the employers and government by continuing the building of the ships. The workers showed they could not be categorised as mindless militants or layabouts.

Second, the campaign did not just confine itself to the yards or other workplaces. While there was a mass sympathy strike, the campaign garnered support throughout communities becoming a movement as the ramifications of closure sunk in. These communities demonstrated this solidarity and self-interest in huge public marches showing the campaign had built a robust alliance of workers and citizens.

Third, there was the language and discourse of the work-in. While the campaign could have easily and explicitly latched itself onto the heritage of ‘Red Clydeside’, instead it deployed other resources. One was that shipbuilding was an iconic industry in the west of Scotland. It was said that men too were built in the yards. This was fully utilised as was the emerging shape of progressive Scottish national identity, whereby the sense of a grievance being done to the whole of Scotland was disseminated.

Reid is acknowledged as the leading architect of these strategies and tactics. He helps provide the left with valuable lessons for today if they want the credibility and respect that is needed to create and lead mass struggles.

These are: talk in a language that workers and citizens understand; don’t necessarily repeat the forms of what has gone before; frame the salient issues in a way that relates to what will work best for the given situation and era; understand that coalitions need to be built with wide arrays of groups outside the usual suspects; and do so in a way that is non-sectarian.

This was what was also done last time round with the poll tax, and these kinds of skills and imagination are desperately needed if the radical left is to be able to step up to the plate this time round.

The text of the speech that Unite general secretary, Len McCluskey, gave in Jimmy’s honour for the second annual Jimmy Reid lecture on 10 October 2013 can be found at

http://reidfoundation.org/2013/10/we-are-not-rats-text-of-len-mccluskeys-reid-lecture/, the archive of Jimmy Reid is held at Glasgow University – see http://reidfoundation.org/2015/05/archive-of-jimmy-reid/ – and a painting of Jimmy makes up part of the mural outside the restored Clutha bar in Glasgow. Lastly, Jimmy Reid wrote a biography called Reflections of a Clyde-build man (1976) and Power without Principles: New Labour’s Sickness and Other Essays (1999) which was a collection of his columns from the Herald.

Gregor Gall is editor of the Scottish Left Review and Director of the Jimmy Reid Foundation